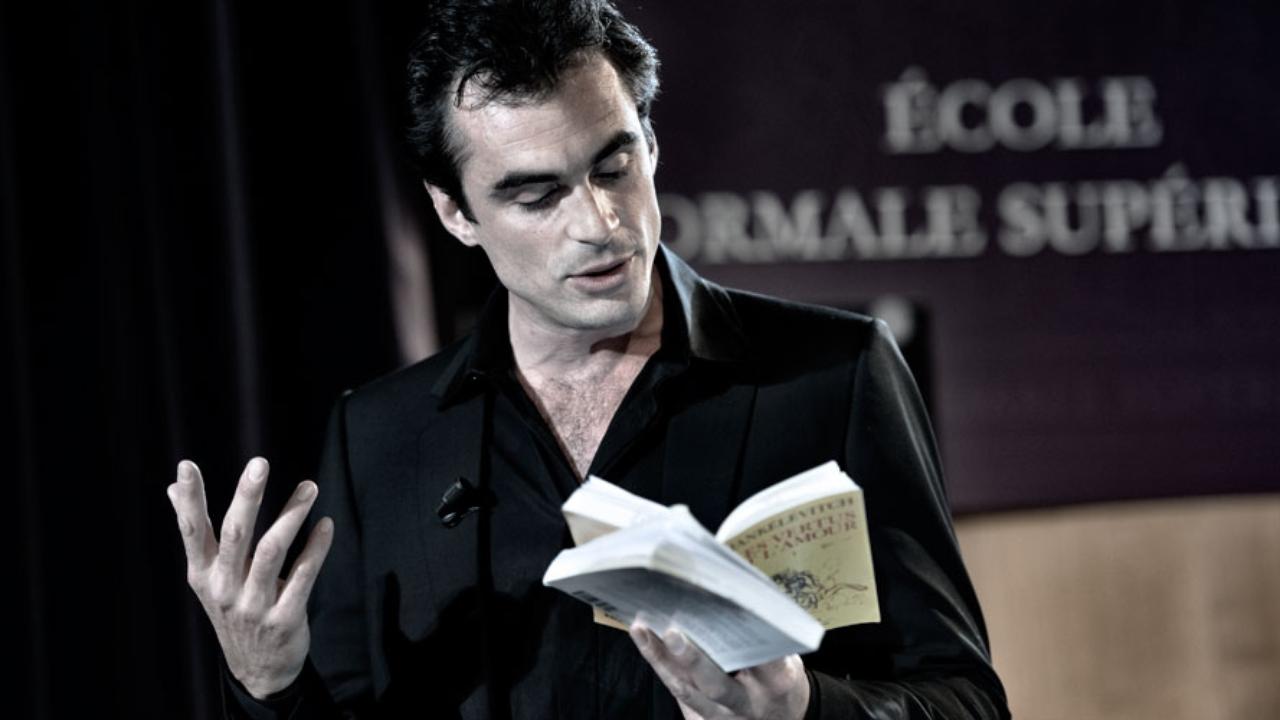

Critic by Raphael Enthoven

THE MEMORY OF A SONG

Socrates was a strange man.

Rich but poorly dressed, polite but not punctual, hideous yet sublime, the father of dialectics was sometimes prone to blindly obeying the whims of a demon, or of a « dream », which, acting as a benine genie, would order him, let's say, to lie down in the shade of an apple tree or, despite his imminent execution, to become a musician. « Socrates ! Become a poet and cultivate music ! » What next?

« Up until now, he confessed in Phaedo, I thought that... in the same way we encourage athletes, the dream spurned me on to pursue my occupation, to practise music ; because to me, philosophy is the loftiest music, and the object of my pursuit. But now that my trial has taken place and that the god's celebration has postponed my death, I thought that perhaps, if the dream ordered me to take up ordinary music, I should not disobey it and should do so... »

A strange urgency. What is the point of becoming a real musician, at this point ?

Why have spent one's life preparing for death (namely by detaching the soul from the body through reflection) only to plunge into affect when the time has come to die ?

But why, conversely, under the pretext that darkness is extending its weight, yield a single inch of terrain to death, while still among the living, and not do exactly what we feel like doing, singing whatever tune we wish to sing?

Is the man whom the nearing abyss leads to begin practising music a madman untouched by reality, or a sage who, here as elsewhere, offers reality no grip ? « One does not learn to die, assures Jankelevitch ; one does not prepare for what is of an entirely different order. What death requires is a preparation without preparations... » Indeed. Time is short. Let us take our time.

Some people practise dying by disavowing their perceptions or by preparing for a possibly long journey. Others (wiser and less foresighted) recognise that life ITSELF does not cease with theirs, and that what is at stake is not surviving their own death, but organizing the happiness of those who will survive them. The first separate the body from the soul, in the same way as a melody escapes from a lyre. The others face up to finitude and mortality, in the same way as a violin left abandoned, a ruin among the ruins of dawn.

Between hope and joy – or between those who desert and those who do not fear the desert - , Li Chevalier has made her choice.

She sides with a form of nostalgia, which has outpaced for ever the certainty of having lost the time and place she pines for. And of a soul whose memories, full of wonder and sadness, discourage one from changing skins.

Here below, heirless instruments, future stones, are already stripped of their strings, legs, and inner song. Rondo logs, the wood of violins merges slowly with dregs of ivory. It happens not unseldom that their crumbled backs offer meager asylum to a man struggling against the wind, or to the muted organ pipes of stalagmites, with a phenix as a backdrop.

Everything seems to speak of death and arrested impetus.

When Li speaks of music, her eyes are dry for having cried too much.

Yet she has offered others a gift of abandon.

And it does happen, now and again, if you listen carefully, that in contemplating her corpses still warm, and feeling the heat dying down, you may hear, in a whisper, the arpeggios of a mineral melody, the lost dream of a well-behaved child – just as Camus, after having dehumanized the world and returned all things to their primordial silence, catches a glimpse of the sky's first smile on an autumn morn in Florence.

It is the distraught idol of a melodious heart. The anamnesis of an intuitive knowledge.

Curbing regret by examining its cause.

Cherishing one's sadness as a living source.

The memory of a song.